Direction of Rotation

Realize next, that the direction of rotation is always from the finger last used, and towards the next finger being used

and you must always supply such rotation with freedom (without an antagonistic muscular pull).

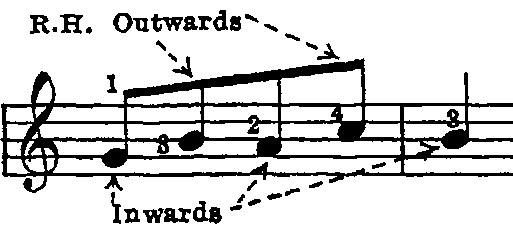

Thus, when a passage alternates upwards and downwards, the rotational stresses are alternately inwards and outwards.

Try the following:

Double Rotation for Passage in the same direction

When a melodic movement proceeds in the same direction, as in a five-finger pattern [C, D, E, F, G],

then you must repeat your rotative stresses in the direction of the passage in the form of double rotation, instead of alternating them.

Now it is easy to realize that in repeating the same note you must repeat the same stress rotationally; yet it is not so easy when you have to repeat the same rotational stresses, but with different fingers.

In a straight five-finger succession of notes, the thumb is executed by rotation inwards towards the keyboard, during the moment of moving the key. But when you follow using the index-finger after it, you must reverse rotation inward and execute a rotation outwards. This is known as a "single rotation", when the index finger rotates outward after the thumb has rotated inwards.

In a straight five-finger succession of notes, the thumb is executed by rotation inwards towards the keyboard, during the moment of moving the key. But when you follow using the index-finger after it, you must reverse rotation inward and execute a rotation outwards. This is known as a "single rotation", when the index finger rotates outward after the thumb has rotated inwards.

For the next note (played by the middle-finger) the index-finger serves as a pivot (from either the surface or depressed level of the keyboard),

and rotation from the index finger to the middle finger is executed. Therefore, you must repeat what you did for the last note.

The ring-finger needs another repetition of the outward rotational-impulse (using the third finger as a pivot),

and the fifth finger requires rotational movement outwards (using the fourth finger as a pivot).

Thus, after the thumb (with its inward rotation) you have four outward impulses using forearm rotation.

When repeating the passage from the fifth finger to the thumb, you must provide four inward impulses rotationally to help these fingers.

Taken slowly, you can show these stresses by actual rotatory movements each time, as directed.

The hand, in this case, turns back (each time) before each rotatory-movement, and then turns again in the direction of (and along with) the next finger you play.

In a quick passage, however, such rotatory-movements cannot be attempted since there is not time for them.

Instead, the rotational movements are invisible and hidden and replaced by finger movements.

Nevertheless, you must supply the necessary help individually for each note by invisible forearm rotative exertions or relaxations,

precisely as you do when you allow actual rotative movements to accompany each note.

Law of Rotation

The law hence becomes dear, that the direction of rotation (whether accompanied by actual rotation or not) is always in the direction of the new finger and away from the last finger. The last finger played becomes the pivot for the new action each time.