Forearm Rotation Effect

Forearm rotation has an important effect upon the finger movements used in piano-playing.

The fingers, as appendages of the hand, can without movement at their own joints, be made to descend and to ascend.

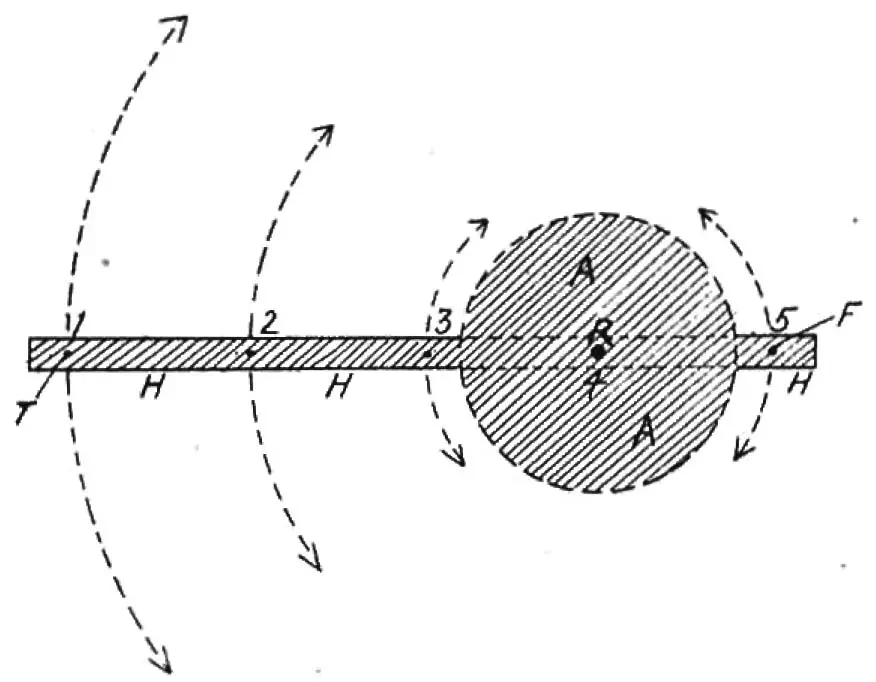

Since the axis of rotation passes through the fourth finger, the thumb will describe the greatest arc because it is furthest removed from the axis of rotation, and the fifth finger, the smallest arc.

The principle is illustrated later, when tremolo movement is analyzed. Movements used to shift this axis to the middle finger or other fingers are described under the wrist-joint .

By using the wrist joint, you can shift the axis to the middle finger or other fingers.

By using the wrist joint, you can shift the axis to the middle finger or other fingers.

Limit of Pronation

The limit of pronation is set by the actual contact of the soft parts and the bones, and supination by the biceps muscle,

the most powerful of the supinators. If the upper arm is permitted to hang freely vertically from the shoulder, and then let the elbow be flexed to a right angle

(the normal position for the pianist is this horizontal forearm), the hand will stand in a vertical, not horizontal position,

an inheritance of the tree climbing ability of our ancestors.

Anatomical Standpoint

From an anatomical standpoint, supination from a vertical hand is the equivalent of pronation from a horizontal hand.

That is to say, a horizontal position of the hand, the extreme position in supination palm up, is the anatomical equivalent of a vertical

position of the hand, the extreme position in pronation (fifth finger up, thumb down).

A piano keyboard, in order to keep this equivalency would have to be built vertically, and a horizontal keyboard, therefore, makes very unequal demands upon the player in regard to ease and range of forearm pronation and supination. This difference, and also the direction of the axis of rotation, as we shall see, affects the piano tremolo in a very decisive way, making the pivoting on the fifth finger much easier and freer than that of the thumb.

A piano keyboard, in order to keep this equivalency would have to be built vertically, and a horizontal keyboard, therefore, makes very unequal demands upon the player in regard to ease and range of forearm pronation and supination. This difference, and also the direction of the axis of rotation, as we shall see, affects the piano tremolo in a very decisive way, making the pivoting on the fifth finger much easier and freer than that of the thumb.

T = position of thumb; F = position of fifth finger; A = cross-section of fore-arm.

Any turning in the axis R will obviously cause a vertical movement at the points T and F, and the farther these points are from the axis,

the greater will be t he range of this vertical movement.

The movement need not be restricted to the thumb and fifth finger.

The movement need not be restricted to the thumb and fifth finger.

As soon as the wrist is turned laterally, the axis no longer passes through the fourth finger, and any finger may be shifted out of the line of the axis of rotation and hence receive vertical displacement when the fore-arm turns at the radio-ulnar joint.As a result or t his motion, the fingers can receive a vertical stroke equivalent In height to the finger-stroke itself (movement in the hand-knu ckle), This touch-type we shall find to be the basis of one form of the piano tremolo.

- The limit of pronation is set by the actual contact of the soft parts and the bones.

- The limit of supination is determined by the bicep muscles.

- If the upperarm be permitted to hang freely vertically from the shoulder, and then the elbow to be flexed to a right angle, the hand will stand in a vertical, not horizontal position.

- From an anatomical standpoint, supination from a vertical hand is the equivalent of pronation from a horizontal hand.

- A horizontal position of the hand, the extreme position in supination (palum-up), is the anatomical equivalent of a vertical position of the hand, the extreme position in pronation.

- For the piano tremolo, the pivoting on the fifth finger is much easier than on the thumb.