Tendonous Interconnections of Hand and Fingers

Tendonous interconnections

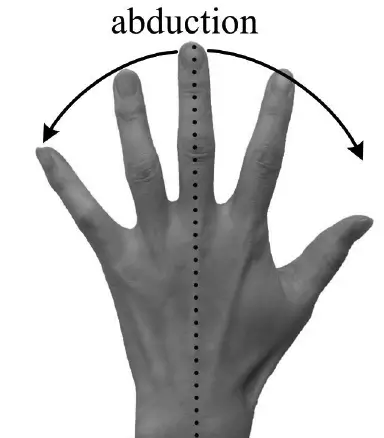

The tendonous interconnections between third and fourth, and between fourth and fifth fingers, account for the tendency of the untrained student to "slur" over passages involving these fingers. Several characteristics of finger-motion deserve mention here. Since the normal finger-position, in regard to lateral motion (1) abduction and 2) adduction), is parallel to the mid-line of the hand, abduction, which is a drawing apart or a spreading of the fingers, requires more muscular effort than adduction, a bringing-together of the fingers. A transition, therefore, from close to open position (diatonic or chromatic progressions to arpeggio), is accompanied by an increase of effort; whereas the reverse transition is accompanied by a decrease.

The practical effect of this is discussed later. The interossei are often treated as 1) flexors of the hand-knuckles as well as of the finger-joints.

This is not true, for we can flex (bend) the hand-knuckles and keep the fingers straight, as in the characteristic position of certain forms of chronic rheumatism (osteoarthritis). If the same muscles performed flexion at all of these joints we should have the paradoxical condition of the same muscle being in states of relaxation and contraction at the same time. For a similar reason the lumbricales[1] do not assist in flexing the two finger phalanges, because we can bend or straighten the finger-joints whether the hand-knuckles be flexed or extended.

Flexion at the hand-knuckle is performed by the lumbricales. Thus two sets of muscles are involved in finger-action,

- one governing movement at the hand-knuckles (metacarpo-phalangeal joints),

- the other, movements at the finger-joints (interphalangeal joints).

Healthy Piano Technique

Two sets of finger muscles:

- abductor-adductor set , and

- flexor-extensor set

Since the same muscle (extensor communis) [2] acts upon both interphalangeal joints, a separate extension of either is normally not possible. This condition does not apply to the thumb, for the extensor muscle here (longus policis) is a separate muscle, for each interphalangeal joint.

For example a spread chord when played on the keyboard cannot be played with the fingers in a vertical position.

[1]lumbricals: The lumbricals are intrinsic muscles of the hand that flex the metacarpophalangeal joints and extend the interphalangeal joints.

[2]extensor communis: The extensor digitorum muscle (also known as extensor digitorum communis) is a muscle of the posterior forearm present in humans and other animals. It extends the medial four digits of the hand.