Contraction Purpose

The purpose of the contraction of this muscle, namely, inhibition of the movements, is revealed also by the time at which it occurs. When the contraction initiates a movement, it obviously occurs at the beginning.

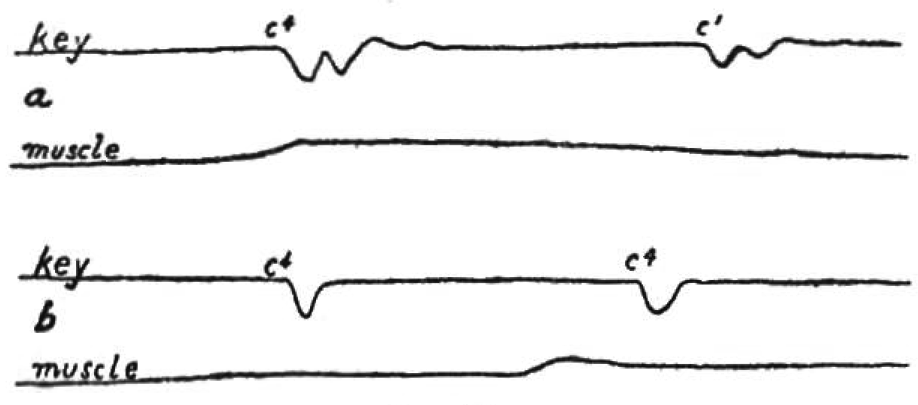

When the contraction retards a movement of any appreciable duration, it occurs after the beginning. In Fig. 35 the duration

of movement is shown between the two deflections in the key-line.

In a) in Figure 35, the muscular contraction coincides with the beginning of movement since it causes the movement.

In b), on the other hand, it inhibits the movement and, accordingly, occurs near the end of the finger stroke.

This manner of muscular contraction is independent of the direction in which the movement occurs. The lower part of the

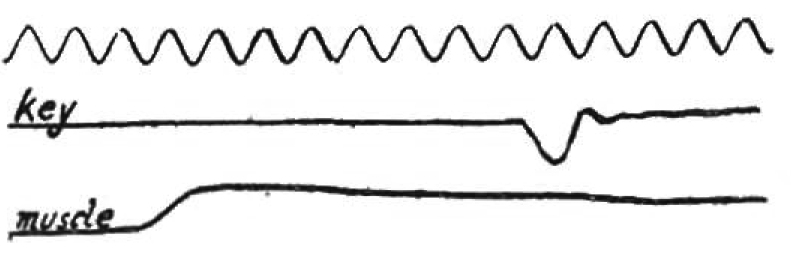

pectoralis major acts as a depressor of the arm. Hence, by holding the pneumatic tambour against the tendon we can record its contraction for arm-descent.

When a chord is played fortissimo, the arm is forced down, the action of gravity being insufficient within the range of movement to produce the desired velocity.

Fig. 36 shows at what part of the stroke the contraction of the pectoralis major takes place in such a vertical arm-stroke. In this particular record sixteen one-hundredths of a second elapse between the contraction of the muscle and the depression of the piano-key.

Moreover, muscular relaxation has already set in by the time the key is reached. This is in agreement with the contraction in lateral arm-movement and points to the initial contraction as typical in all rapid movements.

If this fact holds to be true we may expect to find the time-relationship also present in finger-strokes. These strokes being of considerably less range than the arm-strokes just considered, make the actual time between the contraction of the muscle and the end of the stroke proportionately less. But if the recording be made sufficiently sensitive as to time, the differences may be seen.

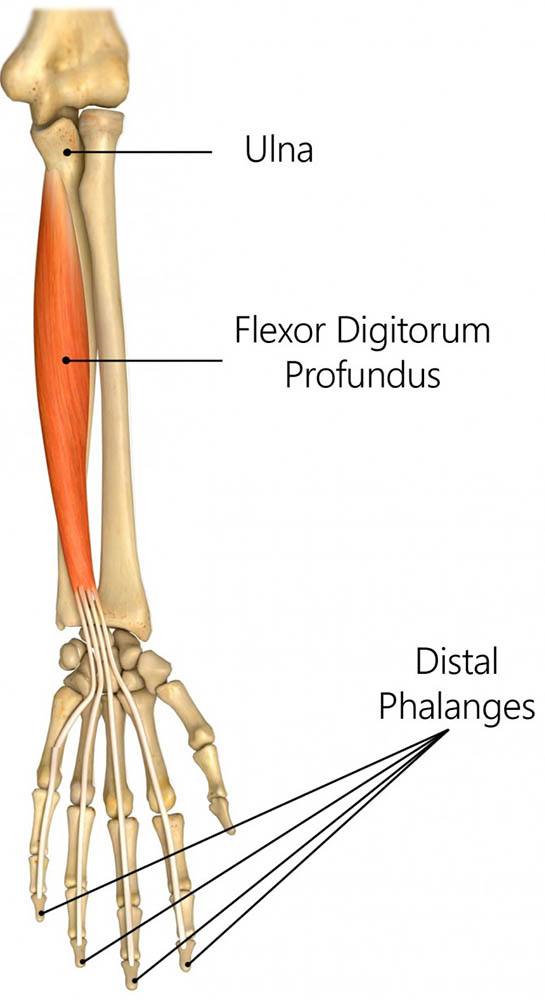

In the figures here given the contraction of the deep flexor of the fingers flexor profundis digitorum [1] was recorded.

This muscle is one of the chief finger-flexors, and its tendon as it passes the wrist is sufficiently superficial to permit recording by the instrument shown in Fig. 29.

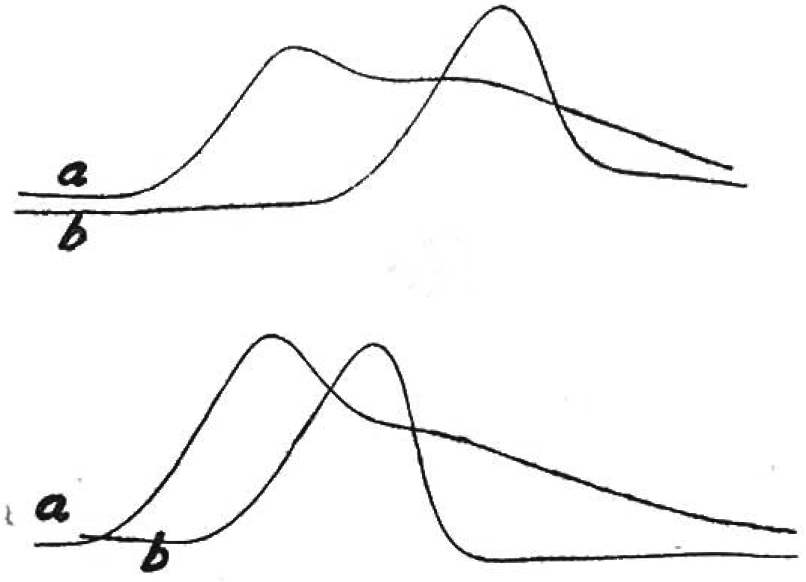

The end of the stroke was recorded by an electric contact. Before illustrating the time-relationships, I include Fig. 37 showing two types of contraction of this muscle, highly magnified. The curves are lettered according to the speed of finger-descent, a, slow, b, very rapid. As the speed is increased the sustained contraction is replaced by the familiar "twitch", followed by a pronounced relaxation.

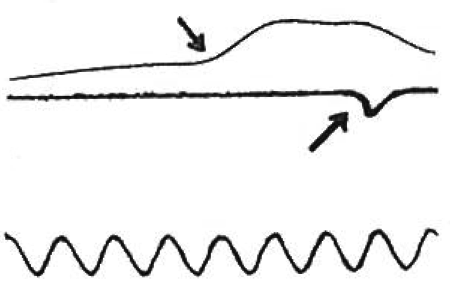

Figure 38 illustrates the relationship between this initial contraction, and the end of the finger-stroke. The upper line in the figure shows the muscle contractions, the deflection in the lower line shows the end of the finger-stroke. Accordingly, in the movements here recorded approximately from two- to three-fiftieths of a second elapsed between the maximum muscular contraction and the end of the stroke. The difference is very small, but some difference was found in all cases. The principle deduced for arm-movements, therefore, holds for finger-movements as well. And in these two physiological units, the whole-arm and the finger, we have the largest and smallest playing-units used in piano technique. Time-relationship between muscular contraction and duration of stroke may, therefore, be considered a basic element of coordination.

The observations on the large muscles with movements of wide range can be made without the use of a recording apparatus, by placing the non-moving hand firmly against the muscle the contraction of which is to be observed. Care must be taken against altering the movement by directing the attention to the expected contraction. For this reason the observation is better made by a person other than the one making the movement itself. But the time interval and the range of the smaller movements are much too small to be detected by general observation. Here a recording apparatus is needed.

Thus far we may formulate the following principles of coordination:

- The time-relationship between the muscular reaction and the duration of a movement is not a constant.

- Muscular contract ion does not parallel the range of movement as speed increases. The faster the movement, the more does the muscular contract ion approach an initial maximal. If twitch" followed by relaxation.

- In all fast movements covering the greater part of the range of movement at any joint, the moving part traverses a part of the distance relatively free from muscular action.

[1]flexor digitorum profundus: Tissue that connects the flexor profundus digitorum to the phalange.