Forceful Movement Large Muscles

The correlation between forceful movements and large muscles, light movements and small muscles is a fact recoguized by all physiologists. Accordingly, as the force increases we may expect to find the larger muscles contributing more and more to the movement .

The pectoralis major is one such muscle. It is the most powerful of the arm adductors and its cont raction is very noticeable in such potential movement s as that represented by pressing the hands together firmly in front of the chest. But it is not the only adductor, and hence does not contract for all movements of adduction. The slower movements of this type do not require the force d manded by rapid movements.

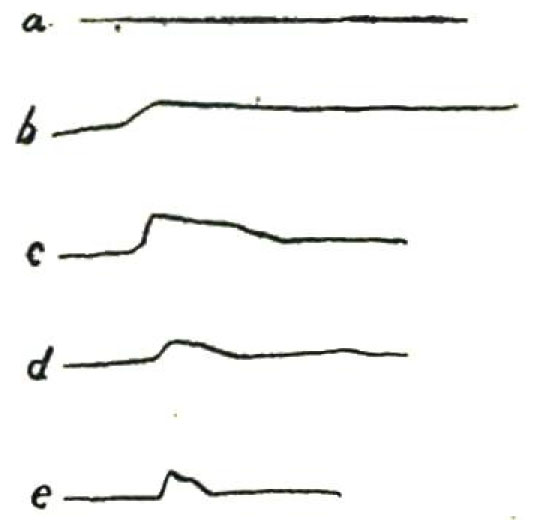

Fig. 33 shows the effect of speed upon the contraction of the pectoralis major.

The movement recorded was a lateral shift of two octaves, from C3 to middle C, with the player seated in the normal position before the keyboard. In record a, the movement was made in one second, necessitating a slow arm movement.

In b, the movement was made in three-fourths of a second ; in c, in one-half ; in d, in one-quarter ; and e, in one-eighth of a second.

Variations in Contraction

No contraction is noticeable in a.

In b the contraction is slight and extends through an appreciable time interval, shown by the horizontal distance covered before the line drops back to the relaxation point. In 0 the contraction is more marked, and of less duration, a relationship shown more clearly in d and e. (Minor variations in these curves should not be used for interpretation since, in all probability they were caused by slight bodily movements and minute, undesirable fluctuations in the air pressure of the recording tambour.) Since in all cases the range and the direction of movement remained constant, and only the speed varied, the changes in the muscular reaction result from these speed variations.

The greater the speed, hence the force required to produce the speed, the more is the work done by larger, more basically situated muscles. Moreover, the type of muscular reaction changes also. When the muscle begins to take part in the movement, it’s contraction is relatively slow and is maintained somewhat. When the speed of movement increases beyond this point the muscle contracts more forcibly, but also more quickly and this degree of contraction is not maintained.

That explains the peaks in Fig. 33d, e, compared to the plateau in b and c of the same figure. It enables the organism to do the same work with less expenditure of energy.

In b the contraction is slight and extends through an appreciable time interval, shown by the horizontal distance covered before the line drops back to the relaxation point. In 0 the contraction is more marked, and of less duration, a relationship shown more clearly in d and e. (Minor variations in these curves should not be used for interpretation since, in all probability they were caused by slight bodily movements and minute, undesirable fluctuations in the air pressure of the recording tambour.) Since in all cases the range and the direction of movement remained constant, and only the speed varied, the changes in the muscular reaction result from these speed variations.

The greater the speed, hence the force required to produce the speed, the more is the work done by larger, more basically situated muscles. Moreover, the type of muscular reaction changes also. When the muscle begins to take part in the movement, it’s contraction is relatively slow and is maintained somewhat. When the speed of movement increases beyond this point the muscle contracts more forcibly, but also more quickly and this degree of contraction is not maintained.

That explains the peaks in Fig. 33d, e, compared to the plateau in b and c of the same figure. It enables the organism to do the same work with less expenditure of energy.