Large Small Muscels

It is at times possible to make the same movement by various muscles, and the question naturally arises as

For example, in a short lateral shift of the hand, let us say of half an octave, should the movement be made by

The question cannot be answered definitely because too much depends upon the precise nature and aim of the lateral shift.

- to which would be considered the coordinated and

- which would be considered the incoordinated movement.

For example, in a short lateral shift of the hand, let us say of half an octave, should the movement be made by

- ab- and adduction of the wrist,

- slight extension and flexion of the elbow with humerus rotation, or

- slight abduction of the upperarm.

The question cannot be answered definitely because too much depends upon the precise nature and aim of the lateral shift.

and upon preceding and succeeding movements. However, the following principle holds:

- a) Rapid movements and b) movements of small range are naturally adapted to the smaller muscles and joints,

- powerful movements and movements of wide range are adapted to the larger muscles and joints.

It is true that large muscles are by no means lacking in the power to control fine movements.

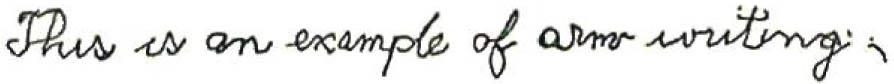

Fig. 39 is an example of writing when an ordinary fountain-pen is attached to the elbow. This necessitates writing with the upper arm entirely, yet, without any preliminary practice, the large shoulder muscles could control the strokes sufficiently to make the words readily legible.

More Economical Work

The fact remains, however, that the work can be more economically and accurately done with the finer finger muscles.

Largely, perhaps, because one element of coordinated movement is proper time.

As soon as a large mass is moved in various directions rapidly, the inevitable factors of inertia and

momentum place the movement in the in-coordinated class.

Rapidly repeated movements, the chief characteristics of which are speed and reversal of direction, play a prominent part in pianistic movements. In keeping with the principle outlined in the preceding paragraph, they should be played with the smallest parts of the arm. Staccato octaves, of weak or moderate intensity should be played from the wrist, using the hand as the moving part.

If played from the elbow, the forearm weight is added to that of the hand and each change of direction must be accompanied by a proportionately greater muscular inhibition. The problems are frequently complicated by other considerations:

Basically, a movement requiring a rapid change of direction in the playing part should be made with as light a moving part as possible. It is for this reason that rapid arm-leaps with reversal of direction are so difficult. The necessary inhibition of momentum interferes with the freedom of the movement. This point brings up the interesting question of whether the pianistic vibrato touch should be classed as

Rapidly repeated movements, the chief characteristics of which are speed and reversal of direction, play a prominent part in pianistic movements. In keeping with the principle outlined in the preceding paragraph, they should be played with the smallest parts of the arm. Staccato octaves, of weak or moderate intensity should be played from the wrist, using the hand as the moving part.

If played from the elbow, the forearm weight is added to that of the hand and each change of direction must be accompanied by a proportionately greater muscular inhibition. The problems are frequently complicated by other considerations:

- ease of reach,

- the character of the preceding and succeeding passages, and

- the dynamic gradations.

Basically, a movement requiring a rapid change of direction in the playing part should be made with as light a moving part as possible. It is for this reason that rapid arm-leaps with reversal of direction are so difficult. The necessary inhibition of momentum interferes with the freedom of the movement. This point brings up the interesting question of whether the pianistic vibrato touch should be classed as

- an in-coordinated or

- a coordinated movement?